Memphis is an American original. Come see yourself in our story when you experience these history- and heritage-related museums, landmarks, parks and trails.

FROM AUTHENTIC RIVERBOATS TO AN UNDERGROUND RAILROAD STOP, A HISTORY "FIELD TRIP" IN MEMPHIS WILL TRANSPORT YOU.

In Memphis, you can trace history from a 15th-century Native American archaeological site to the Rock 'n' Roll and Soul music explosions – and critical chapters in America's civil rights story – of the 20th century. Start in and around downtown Memphis, where you can tour Victorian-era mansions along Millionaire's Row, consider the impacts of agriculture and slavery at The Cotton Museum on historic Cotton Row, take a riverboat ride on the Mississippi and visit a number of music museums that sing the city's sonic history.

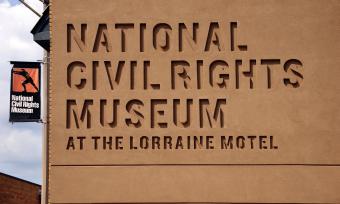

Memphis is home to eight stops on the U.S. Civil Rights Trail, including the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel and Beale Street. But you can also follow the trail to hidden gems like Clayborn Temple, where locals and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. rallied throughout the Sanitation Workers' Strike of 1968. If you only have time for one stop, the Museum of Science & History (MoSH) shares a wide-ranging overview, but for history fans with more time, check out our full guide to Memphis' best history and heritage museums.